2020.10.16 | By Gregory Nagy

The minutes that I have written up for this post are a record of 75 real minutes of conversations during “Hour 10” of the Harvard College course “The Ancient Greek Hero,” which took place “live” on October 13, 2020. A video-audio recording is posted here, with permission from the participants. For this “hour” at Harvard, I as the professor-in-charge chose as the main topic for conversation the celebrated story of a visit to the Land of the Lotus-Eaters in Rhapsody 9 of the Odyssey, where the nostos or ‘homecoming” of the hero Odysseus and his companions is endangered by a loss of noos or ‘consciousness’. But what is really the danger here? In other words, why is the consciousness of homecoming really so dangerous for someone to lose? The answer is simple, despite all the complexities of the story: we must at all costs avoid the loss of the very idea of home—a loss that results from eating the sweet fruit of a plant known in the Odyssey as the lotus. In the previous post of 2020.10.09, I had invited Rick Riordan, author of Percy Jackson and the Olympians, volume 1, Lightning Thief (2005), to comment on the story, in the light of his retelling of that story in the first volume of the Percy Jackson series. In the post for now, we return to Rick’s retelling, in the context of “Hour 10” of the Harvard College course. During this “hour,” Rick was an invited participant in an animated conversation not only with me and with a panel of Harvard College students but also with an intergenerational assembly of other interested readers. In the write-up that follows, as I already noted, I will be presenting minutes, written by me, of the real minutes that we all spent together. During the 75 minutes of that “hour,” we started by concentrating on the Homeric version of the myth about the Lotus-Eaters, and then we followed up by comparing Rick’s version. A dominant theme that extended from one version to the other was the picturing of a historical event, the invention of ether, as highlighted by Rick in minute 14 below. The illustration for my post here reflects that picturing as analyzed by Rick within the time-frame of that single minute 14.

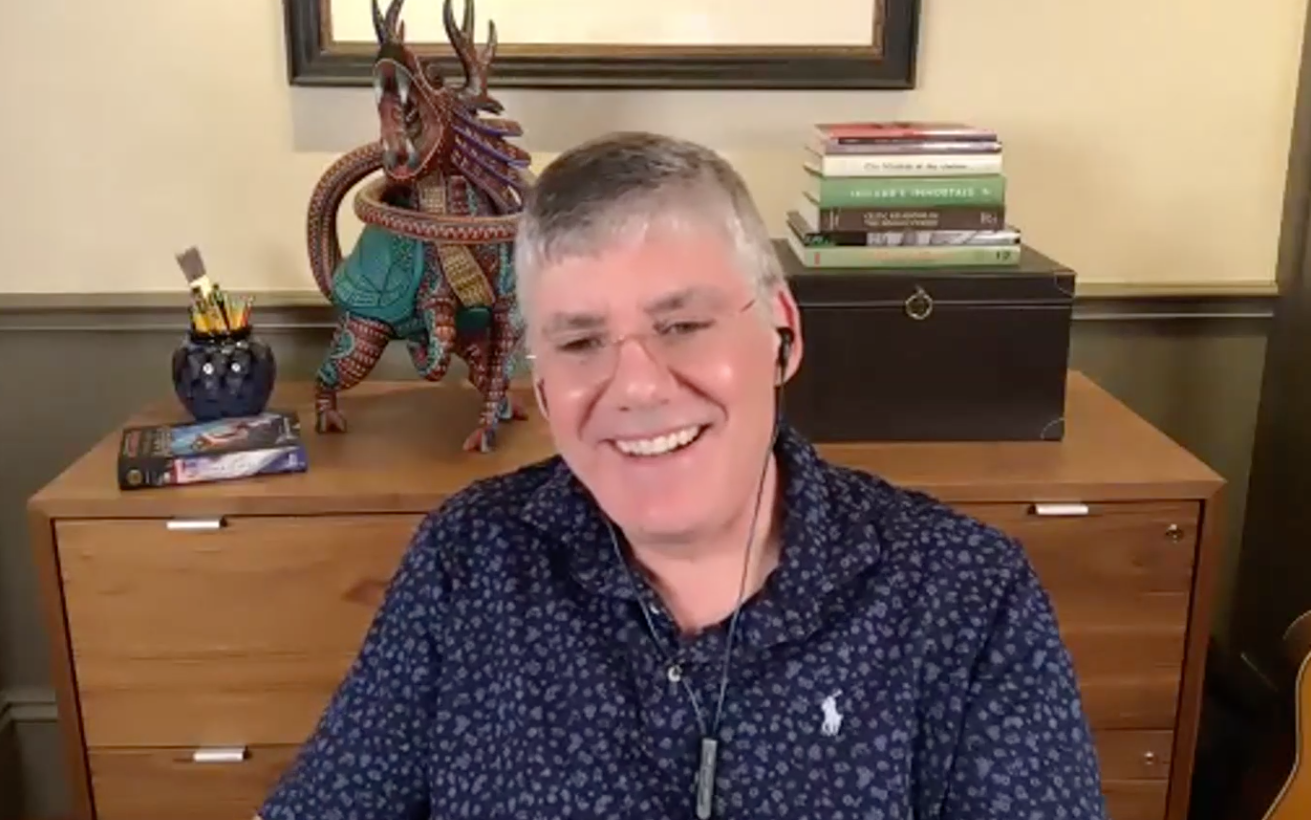

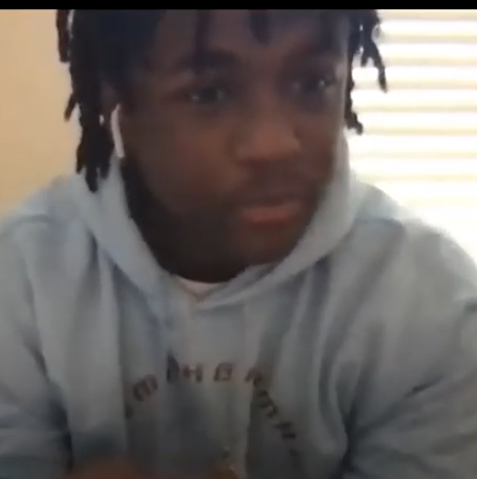

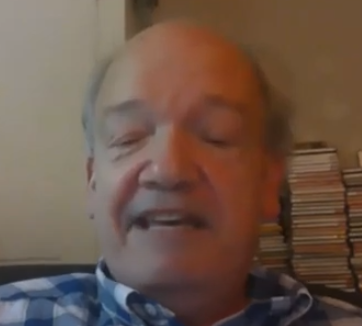

In what follows, each consecutive number indicates the actual minute(s) within which each speaker spoke on October 13, 2020, as recorded here. The names and photographs of the speakers are shown below the numbers for the given minutes.

Minutes

1

Greg introduces Rick. Emphasis on the role of Rick as a teacher, not only as an author. As a teacher in middle school.

2

Greg anticipates that he will introduce at a later point Joseph Nagy, his brother, whose original friendship with Rick had led to Greg’s present friendship with him.

3

Hour 10 is written up in https://www.chs.harvard.edu/CHS/article/display/5952.part-i-hour-10-the-mind-of-odysseus-in-the-homeric-odyssey.

4

The three Harvard College panelists for Hour 10 begin the conversation. Starting with Israel.

5— Israel Benjamin

[For his comment, see the written version here and as recorded in the video-audio.]

(For Professor Nagy) Are there other examples in which a hero like Odysseus has his Kleos and Nostos bound to each other, forcing the hero to achieve both or neither? As with Achilles we saw a big part of his song/epic was the decision to pursue Kleos or Nostos, a very one or the other scenario, especially when juxtaposed with Odysseus.

6

Greg speaks of Orpheus as another example of a hero who achieved a successful nostos from the realm of the unconscious. The hero wins kleos or poetic ‘glory’ for such an achievement. When Odysseus keeps on saying “I saw X” or “I saw Y” in his retelling of what ghosts he saw in the realm of the unconscious, he is being “Orphic.”

7

Greg meditates on the symbolism of the expression “come to.”

8

Keith reminds us that Agamemnon, unlike Odysseus, failed to achieve a successful nostos. Greg notes that there is a symbolic kind of nostos, where you “come to” by returning from the realm of the unconscious and arriving back to the realm of the conscious, but then there is also a realistic kind of nostos, as when you come back home successfully from the Trojan War.

9

Greg mentions his plan to make notes on “Slack” for Harvard College students. This reference to “Slack” is not useful to other readers, however, and other such references will no longer be recorded by me in these minutes.

10

Back to the point made at 8… Odysseus has a nostos, a “coming to,” both in a symbolic way when he comes back from Hades and in a realistic way when he finally comes back home from the Trojan War (even if he is 20 years too late).

11

Joseph Nagy, brother of Greg, remarks to Greg: how come you did not mention Nestor as perhaps the most successful hero of nostos? Greg admits to a mental lapse, a failure in noos. He contritely cites a magisterial work on the subject of Nestor as an ultimate hero of nostos: https://chs.harvard.edu/CHS/article/display/4101.

12— Ainsley Ahmadian

When heroes experience “anesthesia,” how can they ever be sure that they will “come out of it,” that they will “come to”?

[For her comment, see the written version here and as recorded in the video-audio.]

Transition from dark to light: I found the notion of the transition from dark to light very interesting, especially in how it could connect to everyday life. Returning from darkness and death to light and life is not necessarily a sensation that can be found commonly in people’s lives. However, the most death-like unconsciousness that I can imagine based on personal and observed experiences stems from anaesthesia. While this is obviously used for medical purposes, it does induce a temporary loss of awareness that brings about a state of unconsciousness. I would like to consider the mindset before and after anaesthesia in comparison to Odysseus before and after his deep sleep with the Phaeacian seafarers. From personal experience, pre-surgery resembles darkness, a state of physical body in which something is so damaged or destroyed that an induced, death-like state is needed to fix it. Waking up after a procedure, seeing the light and hopefully a gathering of family was a joyful coming-back-to-life that represented the return from darkness/death to light/life. The point I am curious about is that for me and, I would assume most people, we EXPECT the return to light and life after a loss of consciousness with anaesthesia. But in the case of Odysseus and heroes in general who go through this journey, how certain are they, if at all, that after the deep sleep they’ll be in a better place of light and life?

13

Greg thinks… they cannot be sure. That is what makes it all so specially interesting. More about the “scariness” of passing out. Also of “near-death” experiences.

14

Greg keeps elaborating on the symbolism built into the expression “coming to.”

Here is where Rick talks about the statue commemorating the discovery of ether. The illustration for the post shows the statue.

In this context, Rick speaks of the “twilight” experience of a memory blackout. Greg adds an uncanny detail mentioned by Thucydides in the historian’s description of the Plague of 430–427 BCE in Athens (2.49–2.50). One of the symptoms, Thucydides says, was a selective loss of memory. He also says that he had contracted the disease himself, but had survived. Greg’s asks himself: how do we know what Thucydides doesn’t remember in his description? Selective forgetting needs to be paired with selective memory.

15

Another point of comparison: the Plague as described in the Oedipus Tyrannus of Sophocles.

17— Hannah Bebar

On initiatives taken by athletes while competing. Comparable to the mental agility of Odysseus. Especially in the story of his escape from the cave of Polyphemus.

[For her comment, see the written version here and as recorded in the video-audio.]

I really like the idea that you brought up in H24H about Odysseus’ skills and craftiness helping him escape near death experiences. I enjoy participating in athletics and any competition in general. As a player you do not necessarily have all the best physical attributes or skills, but the game becomes a one of mental strategy at the higher level. When I play, instead of just relying on my speed or strength I try to have tactical awareness and outsmart my opponents. However, at times you don’t play with the most awareness, which is the lack of light in the Odyssey, and you have disadvantages. I thought this related very well to Odysseus being stuck in Polyphemus’ cave. Odysseus is smaller, engulfed by darkness, and locked in the cave, but he is able to outsmart Polyphemus and take away his ability to see. This completely destroys any chance of light from reaching Polyphemus. Odysseus again proves that as a skillful warrior he is able to tactically take something away to level the playing field as Polyphemus is physically bigger. In athletics again you have to play to what your advantages are, no matter the situation of opponents or referees or weather. You may not be the strongest, but you can use your intelligence for the game to outcompete others, just like Odysseus did to Polyphemus. I thought it would be interesting to hear what you think about how Odysseus is able to escape near death experiences no matter how much information of light he has throughout his journey back home.

18

Greg says yes, and such initiatives can be described best in one word: noos. In later Greek as spoken by Plato, the word is noûs.

19

Victory in athletic events is symbolic of overcoming a collective death; so, victory is salvific.

20

To coin a term by way of Greek noos: “noetic power.”

21

Greg endorses an intergenerational model for dialogue: people address each other on a first-name basis. Rick says: “I am always Rick to my students.”

22

Greg jumps the gun here, starts mentioning Abigail, but that mention should come later.

Now Greg introduces three “epiphanies”: brother and colleague Joseph Nagy, colleague Rachel Love, and former student Jon Steinberg.

23— Joseph Nagy

First… Joseph Nagy, speaking from home where Greg had once called home. In the same room, urns containing ashes of their mother and their grandmother.

24

Joseph Nagy praises the published research of Rick on the Irish mythological figure Lug; all about returning to light.

25

The epiphanies of Lug are salvific moments; he rescues Ireland from an onset of demons. No need for “Hades” here as the point of transition from darkness to light.

26

On anesthesia for surgery on either the head or the heart: you get “over it” in an abbreviated time, and the abbreviation itself is “sweet.”

At this point, I insert a brilliant essay that Joseph F. Nagy has written about a medieval Irish narrative that closely resembles the ancient Greek narrative about the Land of the Lotus-Eaters:

I am reminded of the scene in the early Irish saga Imram Brain ‘The Voyage of Bran’ where the sea-voyagers, on their way to a supernatural land of women, come across the ‘Isle of Mirth’ (or perhaps a better translation of subae would be ‘Whoopee’), the residents of which, including one of Bran’s crewmates whom he sends to inspect the premises, do not hide in the hinterland, keeping their mirth to themselves. Rather, they appear on the shore, laughing and gaping at the men in the ship, even as the latter desperately circle the island in an attempt to make contact with their lost companion and convince him to rejoin them. The attempt is an abject failure, since, as the text puts it, there is no dialogue or meaningful exchange to be had with these islanders, including their new “convert.” Conversation is key to good relations in all aspects of life, including relations with the otherworldly, in medieval Irish literature, both as it was influenced by Christianity and as it was shaped by a pre-Christian ideological heritage.

And yet, perhaps there is a predictive kind of communication happening here. The people of this “contrary” island are expressing their mocking disdain for Bran and his quest, and for the esoteric connection that he and his men are trying to establish. This is after all not a nostos, since Bran and his men are on their way “out,” having left hearth and home. Theirs is a search, rather, for an otherworld, of which in fact (spoiler alert!) they will grow tired after they have found it, the desire for the wish-fulfilling unknown giving way to an overwhelming wave of nostalgia. . . .

Kuno Meyer’s still-serviceable translation of the Imram Brain is available at:

28— Rachel Love

Second… Rachel Love, who teaches a freshman seminar, “What is a Classic?” Many of her students are attending “Hour 10.” She welcomes the xenia ‘hospitality’ for her manus discipulorum.

29— Jon Steinberg

Third… Jon Steinberg. Took Greg’s Heroes course in 1995.

30

Jon personifies the “middle generation” in this day’s intergenerational group. He passes on his humanism and his appreciation for the power of mythology to the next generation, in the person of his daughter Maddie, age 11.

31— Abigail Gabrieli

Having introduced the three “epiphanies,” Greg turns to introducing Abigail, whom he was already starting to introduce at minute 22 above. Greg first met Abigail 12 years ago. It was she who initiated Greg into reading Rick Riordan’s books on Percy Jackson.

[For her comment, see the written version at Minute 51 and as recorded in the video-audio.]

32

In Abigail’s story, Greg is particularly struck by her reminiscences of her supportive grandmother, who encouraged her love of mythology.

34— Adelia Aldrich

Greg now transitions to his granddaughter Adelia, age 10, who is now the same age, roughly as Abigail was when she had lent her Percy Jackson book for Greg to read.

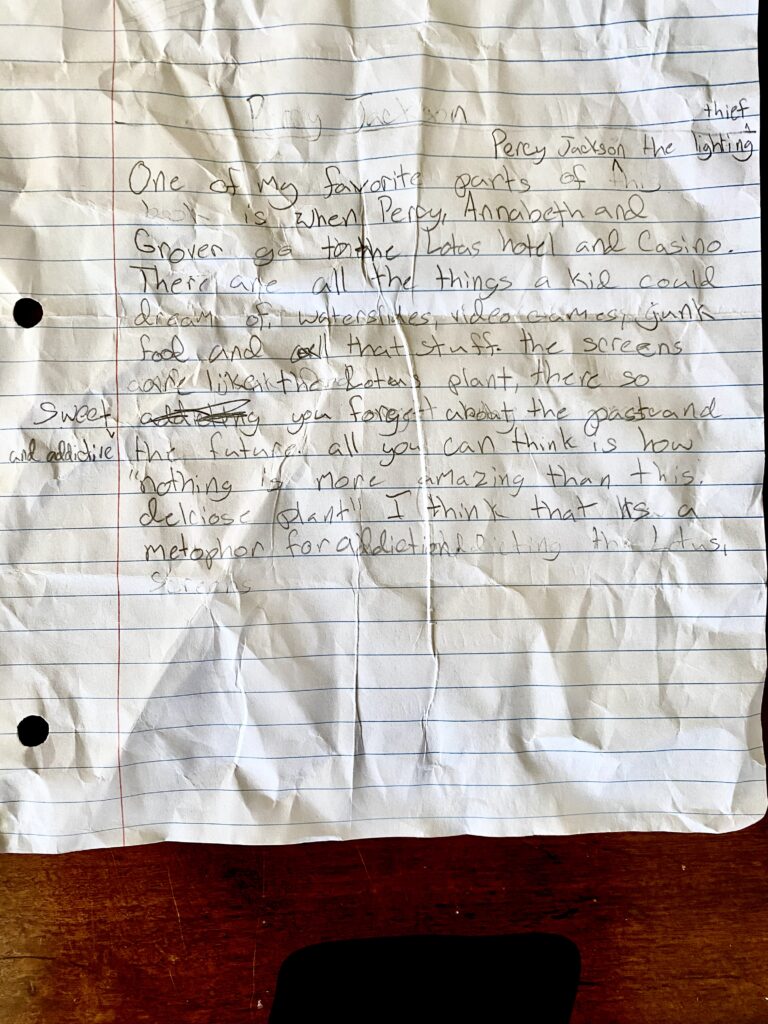

[For her comment, see the written version here and as recorded in the video-audio. Adelia talks about the sweetness of the lotus as a metaphor for addiction.]

35— Maddie Steinberg

Greg now transitions to an intellectual “granddaughter,” Maddie, who is daughter of Greg’s former student Jon.

Maddie talks about the winning mentality of athletic competition, as exemplified by the goddess Nike, and about the parallel mentality of heroes like Odysseus.

38— Aoki Lee Simmons

Greg now transitions to Aoki, who took the “Heroes” course last year.

Aoki speaks enthusiastically about her strong attraction to ancient mythology, and she tells how she petitioned to take the “Heroes” course last year, when lottery was mandated. Greg notes how moved he was by the essay that Aoki included in her petition, where she showed a deep understanding of ancient Greek myths and of the reworkings of these myths in the books of Rick Riordan.

41

At this point, Greg calls for any comments that the three panelists might like to try out on Rick.

42

Israel asks: Percy, Annabeth, and Grover, and their experience at the Lotus Hotel and Casino mirrored to the experience of Odysseus with the Lotus-eaters, but I wanted to ask what is it about the question of what year it was that led you to use it as the decisive point for Percy in the Lotus Hotel?

Rick responds, playfully: I don’t remember. But then Rick elaborates… what shakes Percy out of his apathy is the jarring thought that he cannot remember the name of his mother.

43

It is jarring, to be pulled out of time.

44

The idea of lost time: how long have we been here, anyway? How to restore “lucidity”? [[Greg highlights Rick’s apt wording here.]]

45

Ainsley comments on the euphoria of drug-addiction, and Hannah adds relevant comments about the vicious phases of non-knowing.

[For their comments, see the written version here and as recorded in the video-audio.]

Ainsley: This is a comment that my fellow panelist, Hannah, and I have for Professor Nagy and Rick, as it relates to the lotus flowers from the casino scene as well as the island that Odysseus is trapped on. The notion of the lotus flowers is that they tricked Odysseus into a state of forgetfulness and addiction, keeping him trapped in a certain place and unable to escape due to an induced unwillingness to leave. A parallel we found to this in the realm of athletics is performance-enhancing drugs. These drugs, like the lotus flowers, create a dependence and take away the use of natural ability or judgement. An addiction to the feeling is characterized by the lotus flowers and performance enhancing drugs. When an athlete finds themself winning and having more success with drugs, they’ll be pulled into dependence on the drug, and a general inability to escape the cycle. With the lotus flowers in the casino scene, eating the flowers became second nature to the patrons, who were in the addictive and unknowing cycle. They never would want to leave the casino because of the induced euphoria that was caused by the addiction to the lotus flower, and the forgetfulness of their natural state of mind.

Hannah: In the end, any addictive substance that keeps a person in a vicious cycle of use and repeat, there is always a withdrawal and destruction. There is no ability for a person to break the cycle without harming themselves and the need to rebuild their life, like Odysseus did when he finally escaped the lotus island. That being said, in both the lotus casino segment of the book as well as Odysseus on the lotus eater’s island, the escape from the trance of the lotus flowers seemed relatively unopposed and independent from outside help from the gods. Whereas in real life, getting out of the cycle of an addictive drug is usually quite a difficult battle that involves outside assistance. I would like some insight into how Odysseus and Percy were able to use their own judgement, even under the influence of the lotus-eaters, to escape and help their friends/comrades escape.

46

The comments lead to further thinking about the word noos.

47

Rick finds the symbolism of this word most relevant to understanding the minds of young people who are said to have “learning disabilities” – Rick prefers to say “learning differences.” How to understand divergent thinking? That is what the Percy Jackson stories are really all about, Rick says. Greg agrees that the word noos is most apt here.

48

The power to adapt is a strength, not a weakness. And that power is noos. Finding the side-angles is what the noos of Odysseus is all about.

49

Greg returns to the genial formulations of Ainsley and Hannah in minute 45. He suggests that we not use the word “cycle” in referring to the phase of addiction, in that “cycle” can have a positive symbolism, as when you circle back to your old self.

50

Ainsley and Hannah and Greg all agree that “playing with symbols” can be creative. Rick agrees as well, noting for example the symbolism built into the word “recovery.”

51

Abigail makes some incisive comments on Rick’s books. Greg notes especially her views, very clearly articulated, about the role of family in shaping the very idea of home. Greg asked Abigail to write up her thoughts, and he quotes here two paragraphs that Abigail has written up to summarize:

§1. I was struck by the way in which the Percy Jackson books connect ideas about family, noos, and nostos in the Lotus Hotel scene. It’s Percy’s thoughts about his mother – his horrifying realization that he has almost forgotten her name, and then his ensuing memory of the danger she faces and his quest to rescue her – that inspire him to struggle to break free and come back to his proper consciousness. Further, in falling prey to the lure of the Lotus Hotel and losing his awareness of home, Percy fundamentally endangers his capacity ever to reach that home: he forgets an important dream he had about his mother and nearly runs out of time to rescue her. The incident thus draws attention to the way family is crucial to Percy’s understanding of home. Percy’s mother is what makes his home home. The Lightning Thief would not be the story of a successful homecoming if Percy returned to New York but Sally remained in Hades. In the book, Percy is on a dual quest: both the pursuit of Zeus’s master bolt (his nominal heroic goal) and the retrieval of his mother (his real goal). Thus, like Odysseus’s, Percy’s is a tale of nostos; but Percy also needs to reconstruct that home by rescuing his mother and carrying out his secondary quest, in which he establishes the heroic identity that defines him for the rest of the series. That complication makes for an interesting comparison to Odysseus, who, as discussed in Hour 10, actually needs to experience the psychic nothingness of the episode with Polyphemus that constitutes a rejection of his past heroic kleos in order to achieve his homecoming.

§2. I found the question of how people are able to break free from the lotus eaters a particularly interesting way to think about heroic agency, as well as the interconnection between family, noos, and nostos. It’s not just the central protagonists who break free, after all – indeed, Odysseus, unlike Percy, doesn’t even eat the flowers and confront the ensuing heightened temptation at all. When discussing Percy Jackson, we focused a lot on how Percy himself breaks free, with his thoughts about his mother, which remind him of both his quest and his nostos – but there’s also Annabeth (who breaks free when reminded of her great fear – spiders! – which itself is inherited from her mother, Athena); Bianca and Nico (who are physically removed – although again with a family connection); and Grover (physically dragged out). Grover being physically pulled away as a piece of comic relief seems most closely to parallel how the episode progresses in the Odyssey, where Odysseus makes his men come back “using force”, “dragging” them back to the ship and “tying them to the benches.” Like Grover, these individuals don’t seem to exercise much personal agency; they don’t get to experience a heroic restoration of consciousness, a “coming to” in which they themselves restore their awareness of nostos. An interesting further comparison might be to the episode in the Odyssey in which Odysseus lashes himself to the mast when listening to the Sirens: here, he’s using physical compulsion to ensure he doesn’t give in to a lapse in his consciousness of the quest for homecoming, but in a fashion that affords him far more agency than his shipmates or Grover.

54

Aoki agrees with Abigail… The idea of “home” is built into the family, even if the family is not static but on the move.

56

Rick likes Greg’s meditations on the Modern Greek adjective nostimo-, in the sense of ‘delicious’. This word is derived from ancient Greek noun nostos, which has nothing to do with cooking. But the adjective still implies “home cooking.” Greg adds: “home sweet home.”

57

Greg notes Rick’s acute analysis of the illustration in the post of 2020.10.09. Rick summarizes what he wrote in the annotations for that post.

60

Maddie has more to say about the symbolism of addiction.

62

Jon comments on perceptions of dominance in the picture analyzed by Rick.

63

Greg calls on Rick to summarize.

64-67

What Rick says, in these three minutes, is so exquisite, in Greg’s opinion, that it has to be heard in its entirety from Rick himself in the video-audio. A true high-point.

70-73

Abigail adds incisive comments that are written up in paragraph 2 of what I quoted from her at minute 51. With strong support from Aoki.

74

Greg does not want to end the session, since it has been so pleasurable for him.

75

Greg says: “I don’t want this to end.”